The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

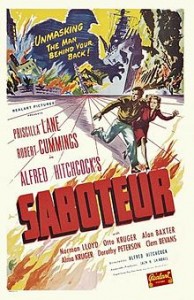

Synopsis: Los Angeles aircraft worker Barry Kane evades arrest after he is unjustly accused of sabotage. Following leads, he travels across the country to New York trying to clear his name by exposing a gang of fascist-supporting saboteurs led by apparently respectable Charles Tobin. Along the way, he involves Pat Martin, eventually preventing another major act of sabotage. They finally catch up with Frank Frye, the man who actually committed the act of sabotage at the aircraft factory.

James: Saboteur is one of my favorite Hitchcock films. I’ve seen this one and the next one, Shadow of a Doubt, more than any of his films. There’s a lot to this movie, so I’m looking forward to this discussion.

Jason: Very interesting, my friend. Although I enjoyed this film, I don’t think I’d call it one of Hitch’s most effective. Don’t get me wrong, there are many things I liked about it, but if you step back and look at it, it’s a big, somewhat slow, sprawling piece of war propaganda. (I also thought it was interesting how in Hitchcock/Truffaut, Hitch says that this film lacks discipline. He thinks there’s too much going on. The man can be quite self-critical.) And I lost count of how many patriotic speeches and asides it contains, and after a while they negatively affected the film for me.

James: This time around, I did notice the propaganda speeches. There seemed to be more, but they still didn’t bother me. Nothing like that tacked-on ending to Foreign Correspondent. It felt right when the head saboteur Charles Tobin (Otto Kruger) was talking, but it felt wrong when our heroes Barry Kane (Robert Cummings) and Patricia Martin (Priscilla Lane) were talking together.

Jason: I actually liked the way the propagandist ending was tacked on to Foreign Correspondent, almost as a final “Here we go!” statement as the war was starting. It felt like a great rally cry and didn’t really affect the story. I found it amusing. Here, the propaganda is spread throughout the film, in much of the dialog, so that it defines the entire narrative. It’s more omnipresent. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it definitely places the film in a specific time period and mentality, so it feels more dated Foreign Correspondent to me. That’s fine. It’s a product of its time. But I don’t consider it a “pure” narrative, you know? It’s too influenced by outside forces. Here’s one line of propaganda that I have in my notes: “A man like you can’t last in a country like this.”

James: But I think it’s okay, because I got the impression that at the time, everyone was very concerned about the country. Just like everyone was patriotic after September 11, 2001.

Jason: All that being said, this film has some big, great scenes. It’s like it’s got all the components of a spectacular film—and it really feels like the first of his big American movies—but it feels overly long and political to me, and I was never really riveted by the stars. And you know, it just felt like he’d done it all before. I was constantly reminded of The 39 Steps, in which I think he does this same plot better, and even Foreign Correspondent, which I enjoyed more.

Jason: All that being said, this film has some big, great scenes. It’s like it’s got all the components of a spectacular film—and it really feels like the first of his big American movies—but it feels overly long and political to me, and I was never really riveted by the stars. And you know, it just felt like he’d done it all before. I was constantly reminded of The 39 Steps, in which I think he does this same plot better, and even Foreign Correspondent, which I enjoyed more.

James: You’re right, I’m getting a little tired of Hitch always borrowing from his earlier films. But I wonder if it has to do with his audience (which is new, now American). Combine that with the improved filming techniques and technology. Maybe he just figured he could do it better now, for a new audience, so he went with it? Or maybe he didn’t like the way it worked in earlier films so he decided to try again.

Jason: That’s a good point. I even read something to that effect in the biography I’m reading. But I guess my point is that he’s already done an essential remake of The 39 Steps in Foreign Correspondent (and in fact, he’ll make yet another one in North by Northwest). I guess I don’t really find it irritating as much as interesting and a tad frustrating.

James: I really appreciated the gradual romance in this one. I thought to myself that this is one of the more natural, realistic growths in that department of any of the Hitchcock films (at least, those that I can remember). Pat slowly grows to love Barry as she learns that he’s not the bad guy. The two go hand in hand, which helps make their relationship that much more real. I understand the need for quick romance in some of his pictures, but here it works perfectly.

Jason: Once again, I was wondering what you must be thinking as this one developed. And I too thought the romance was well drawn, in a very natural progression. But still, it was an awful lot like the romance in The 39 Steps, even including handcuffs and fleeing across the countryside. Just as in that film, the woman at first is angry with the man and thinks him guilty, but slowly warms to him and falls in love with him. Am I wrong to be a little bothered by the fact that Hitch seems to be so obviously borrowing from his previous work? Well, I guess I wouldn’t say “bothered,” but it was definitely at the back of my mind while watching, to the point at which I could predict, in general, how the film would end.

James: You make a good point.

Jason: Anyway, let’s get to it. First of all, I really liked the death scene of Barry’s buddy Ken in the flames early on—the first sabotage. The model work was really convincing, even when Ken fell amidst the flames. And the later knowledge that the real saboteur, Frank Fry (Norman Lloyd), handed Barry a fire extinguisher filled with gasoline is horrifying.

James: That opening scene is great. That opening fire had a good feel to it.

Jason: I loved the way the smoke crept across the screen, blacking it out. Very effective.

James: Since this was the first time you saw this film, did you immediately know that Tobin was a bad guy? It’s been so long that I can’t remember, but I thought Hitch did a good job making him feel just slightly slimy.

Jason: I had a feeling about Tobin, but you’re right, the grandfatherly touches and his relaxation were terrific. I still had my doubts about him. And as we come to understand him, he becomes really sinister.

James: There was something wrong with him from the beginning, yet at the same time, he seemed to be a good enough guy. A caring grandfather, for example. He was at once an upstanding citizen, yet he was also a criminal against the nation.

Jason: I did like Tobin as a villain. He had a great Vincent Price quality, and I always like well-spoken villains. Getting back to the scene by the pool, there were several things I liked about that. First, I liked how the baby unearths the telltale telegram, out of her grandpa’s jacket pocket, and that’s the moment we know Tobin isn’t at all what he seems. So even at the moment of discovery, his evil is tied with the innocence of his grandchild. In the same vein, I liked how Barry uses the kid as a human shield to escape the compound. There’s something very fitting about using that symbol of innocence, Tobin’s main weakness, as a means for escape. Nice escape on horseback afterward, too.

Jason: I did like Tobin as a villain. He had a great Vincent Price quality, and I always like well-spoken villains. Getting back to the scene by the pool, there were several things I liked about that. First, I liked how the baby unearths the telltale telegram, out of her grandpa’s jacket pocket, and that’s the moment we know Tobin isn’t at all what he seems. So even at the moment of discovery, his evil is tied with the innocence of his grandchild. In the same vein, I liked how Barry uses the kid as a human shield to escape the compound. There’s something very fitting about using that symbol of innocence, Tobin’s main weakness, as a means for escape. Nice escape on horseback afterward, too.

James: Using the child in the pool scene was perfect, particularly the way Barry puts her down as he escapes. While I certainly don’t look into things as deeply as you do, I just thought it was interesting to note that Barry is such a good guy that he puts her down safely. He considers Tobin to be completely evil, but there’s still a part of Tobin that’s human. He’s the grandfather of this young girl, and Barry puts her down safely to return to the family.

Jason: Yes, that was a good moment, Barry setting that kid down. Tobin has a good, creepy team, too. Not only Fry, but that henchman Freeman (Alan Baxter) is one queer fellow, even more creepy than Tobin: “When I was a boy, I had long, golden curls.” I wonder if that comment is supposed to suggest homosexuality.

James: Yeah, that Freeman guy is an interesting fellow. That scene actually always creeps me out. There’s something wrong with the way he mentions his golden locks. Maybe he’s gay, maybe not. It’s just creepy. But I kind of got the impression that he’s trying to attain Tobin’s level of, I don’t know, leadership maybe? Tobin is this great man, supposedly. He has followers. I got the impression that Freeman was saying that, at one point in time at least, he was the center of attention too.

Jason: I just wouldn’t put it past Hitch to make it some kind of kinky sexuality statement.

James: What do you think of the scene at the cottage, with Pat’s blind uncle, Phillip Martin (Vaughan Glaser)?

Jason: At first, I was reminded of the very similar scene in Bride of Frankenstein, when the monster stumbles upon the blind man’s cottage for refuge, and ends up eating and drinking with the man, who is a similarly gentle, well-spoken soul. That was a cool parallel. But in this one, the old man’s speeches sort of began to bug me, as far as their propagandist platitudes. He was too gentle, too understanding, and you could tell that he was speaking in symbolic terms, not like a real human being would speak. He was representing “benevolent” America, I think.

James: I’m a bit surprised you didn’t bring up the whole “seeing” thing Hitch has going. I mean, this man is blind yet “sees” better than anyone else in the film. I liked that touch. It was a tad heavy-handed and a tad saccharine since he’s so perfect, but it was nicely done.

Jason: I took note of the blind man as the character who “sees” the clearest, but I didn’t know how to bring it up. I’ve been thinking about it, because it’s a reversal of the way vision has been used by Hitch in the past. Where before characters with vision problems didn’t see things clearly, in this film it’s the exact opposite. So I guess that’s the interesting aspect. In this film, I think for the first time, the symbolism is used ironically.

James: Actually, now that I think about it, the circus freaks have that same feeling. These people are outcasts and can see the good in others, whereas the rest of the world is ready to burn Barry for something he didn’t do. What’s Hitch trying to say here?

Jason: Ah, the circus freaks. Now here’s what I took from that scene—and in reality, it’s essentially spelled out for us by the “skeleton man,” Bones (Pedro de Cordoba). As soon as I saw the midget with the mustache (Billy Curtis), I thought of Hitler. And I realized that the troupe in that caravan is a microcosm of the international relationships among the nations involved in the war.

James: I too recognized the midget as Hitler, but I didn’t take the step to thinking the rest of them as other countries. That’s interesting.

Jason: This is no great revelation, because as I said, Bones essentially lays it out for us, but I thought it was interesting. I don’t know which character stands for which nation, but it’s an interesting scene, in that light.

James: Maybe my favorite part of this film is the billboards Barry keeps seeing. The signs continually tell him something, while at the same time making sense as advertisements. “You’re being followed,” and “Beautiful funeral” . . . I loved it.

Jason: That was a nice touch. But I noticed the messages on them only once, so I didn’t make that full connection. That’s cool. Worth rewatching.

James: I just thought of something. What becomes of the dam? Do they just leave that job? I know they don’t blow the dam, but I don’t remember the reasons for not doing it.

Jason: Speaking of the dam, I really liked the way the couple discovered the target. The hole in the wall, the tripod, the telescope—the dam is what the saboteurs are after! Nicely done. In fact, I liked that whole ghost-town sequence. But yes, there’s a throwaway line later, in which someone says, “We already had to abandon the dam project” or something. It felt to me as if Hitch liked the idea of targeting the dam, and liked filming it, but he couldn’t think of a way to bring it into fruition—that is, blow it up or actually film scenes there. Maybe it was just easier to film at the Navy shipyard later.

James: Yeah, I really enjoyed the ghost-town scene too. It was well executed. I would’ve liked to have seen Pat being chased though. Or something. I never felt she was any real danger, and I think it would’ve been a nice touch to maybe see her get in trouble.

Jason: I agree about the aftermath of the ghost-town scene. The way she just disappeared from the next room and then appeared safe in the next scene was abrupt. And I didn’t expect Barry to drive east with the saboteurs. The film seemed to abruptly change gears right then—just after Pat disappears from the ghost town. It was a jarring transition into the next act and seemed sloppy.

James: I’m not sure what else you want from that scene. It’s true that I wanted to see her being chased or in danger, and we didn’t get it. But as far as Barry is concerned, I think that was the only way to get him into the beehive, so to speak. How else could he infiltrate the group? I liked the way it worked out that Pat thought he was lying to her and not to the bad guys.

Jason: I guess the transition to New York just felt too abrupt to me and left me a bit confused. Pat’s suddenly out of the picture, having apparently escaped, and Barry’s making the odd decision to drive thousands of miles back east. Seems like he could’ve talked his way out of that, but the plot demanded that he go along for the ride. Hmmm, not a really big deal, but it stretched believability for me.

James: You know what was missing in Saboteur? The witty banter. Those funny one-liners. Barry’s character really isn’t the type to deliver those lines so it isn’t a mistake, but it did make this film a little less fun.

Jason: Yes, there was a real lack of wry humor in Saboteur. I missed the Robert Donat-style fun. Although I liked the scene with the truck driver. He had some good lines—“You married?” “No.” “Go ahead and whistle.”—and I liked the way he reappears later to save Barry from the cops. And while we’re at that point in the movie, how about that great jump from the bridge? Nice to see an actual location shot and a real physical effect. That was a great scene, but it was the beginning of a “handcuffed-and-on-the-run” scene that’s so reminiscent of The 39 Steps. Even as far as hiding out near a waterfall.

James: That jump scene was great. What was even more impressive than being on location was the fact that it wasn’t a dummy. Or rather, if it was a dummy, it wasn’t totally obvious. In Foreign Correspondent, the dummy dropping through the awning is obvious. Even at the beginning of Saboteur, it’s clear that it’s a dummy in the fire. This scene has a real Indiana Jones flavor for Hitchcock, and I liked the solid action that can only come from being on location.

Jason: Yep, it has a real sense of adventure.

James: I got a laugh out of the scene on the road just after Barry cuts off the cuffs. The old couple thinks the two are madly in love. That’s hilarious.

Jason: Another bit of humor also echoes The 39 Steps: Barry is forced to give a speech about someone he doesn’t know, this time in the ballroom filled with guests.

James: I forgot to mention that speech. It definitely mirrors The 39 Steps. I thought that immediately. And of course, there are stairs in that ballroom scene, too.

Jason: What did you think of the ballroom scene, overall? This is one of my favorite sequences in the film. It seems to encapsulate a lot of vintage Hitchcock. You have fear mixed with romance, as Pat and Barry’s love comes to a head and the place fills with bad guys wanting to surround and capture them. I like the way they feel trapped and doomed, and no one around them is aware of anything. And everyone laughs at them when they suggest the place is a den of sabotage.

James: Hitch certainly likes ballrooms, doesn’t he? They’re everywhere. I find it interesting that everyone thinks Barry’s drunk. Plus, he’s in a suit and tie and he’s under-dressed. And how he must let her dance with that guy who cuts in because otherwise it would be rude. Gotta love the old days. But yeah, I agree, this was a great scene. I also enjoyed how the pair gets away from the parlor upstairs. The servant comes in and they just sneak out with her.

Jason: What I like best about the parlor scene is the way Barry points at the book title Escape as a message to Pat, who’s sitting nearby. Then Tobin uses the same trick to describe Barry’s fate: Death of a Nobody.

James: I thought it was funny that Pat never catches on to him pointing out Escape. But you’re right, it was a nice touch to have Tobin work that into his threat.

Jason: That was really a great, ominous touch.

James: How about the movie-theater sequence toward the end of the film? You couldn’t quite make out who was talking and whether the gunfire was coming from the movie within the movie. Great stuff.

Jason: The theater sequence reminded me instantly of Sabotage, because I was looking for parallels from the start. But this was an obvious lift, all the way to the audience laughing inappropriately at the onscreen violence. The whole film-within-a-film commentary is here, but not as subtle as in Sabotage. Again, I think he did it better in the earlier film. Or at least it was less obvious and therefore didn’t feel like it was calling attention to itself. I did, however, enjoy how the gunplay on the screen echoed the gunplay in the theater.

James: I did indeed think of Sabotage during the movie scene. Hitch loves theaters, doesn’t he? But it seemed that this scene was the exact same idea as the earlier film, just a bit more obvious and a bit more vibrant.

Jason: Here’s a question for you. The sabotage that actually happens—the explosion in the shipyard— was very confusing to me. I got the distinct sense that the exploding bomb missed the boat, and yet when Fry is driving past the shipyard later, the boat is capsized. What the hell happened there? And what was with the photographic technique of shooting those people from head to toe with looks of surprise? That looked totally low-rent.

James: Oh yeah, the capsized ship. That effect was terrible. I assume it was supposed to show those passengers being thrown in the air? I too thought the explosion occurred too late, and thus the ship was saved. If the ship did indeed sink, then that means the hero didn’t prevail, which doesn’t feel right. The hero shouldn’t fail.

Jason: See, to me, that’s a major problem with the plot. Did the saboteur succeed in sinking that ship, or did he fail? That’s completely unclear. I gather from this biography I’m reading that Hitch decided to use real-world newsreel footage of the capsizing of the Normandie for the scene in which Fry smirks from the taxi. I think Hitch was smart to capitalize on that footage, but maybe he didn’t really pause to think whether it made sense in the narrative. Hitch got into a lot of trouble with the Navy for implying that sabotage brought down the Normandie, by the way.

James: I think the Navy was out of line. I don’t know how outraged they were, but c’mon, it’s a movie. I think Hitch was fine doing it. If anyone actually thought that the Normandie was indeed sabotaged because of this movie, then that person is an idiot.

Jason: True, but I think the Navy was just concerned about public perception in a time of war. And we know by now that it’s a given that people are idiots.

James: I liked the Statue of Liberty climax. Especially how Fry’s sleeve unstitches very, very slowly as he’s hanging from the statue’s torch. Sure, you know he’s going to drop, but it’s tense nonetheless. The torch effect is a bit wobbly, though, which made it hard to suspend my disbelief. I’ve always found it interesting in these types of movies, and even in Disney movies, that the killer or bad guy always dies at the end because of the hero, but not in an overt way. Barry “accidentally” forces Fry over the edge. The hero always does the killing, but it’s always an accident.

James: I liked the Statue of Liberty climax. Especially how Fry’s sleeve unstitches very, very slowly as he’s hanging from the statue’s torch. Sure, you know he’s going to drop, but it’s tense nonetheless. The torch effect is a bit wobbly, though, which made it hard to suspend my disbelief. I’ve always found it interesting in these types of movies, and even in Disney movies, that the killer or bad guy always dies at the end because of the hero, but not in an overt way. Barry “accidentally” forces Fry over the edge. The hero always does the killing, but it’s always an accident.

Jason: Yeah, the whole Statue of Liberty climax is terrific, and I like how it foreshadows Hitch’s use of other national monuments, like Mount Rushmore. It’s perfectly in line with his predilection for big-setting endings, and in fact I caught what might be an in-joke at the police station, when the chief orders his men to go to the Statue of Liberty to apprehend Fry, and one of the men says, “He wouldn’t go there! He’s on the run,” and the chief says something like, “Remember when we caught Schultz at the modern art museum? Remember when we got Renaldo at the fish aquarium?” I thought those might be references to past Hitch films. For example, I know we had a climax in an art museum in Blackmail.

James: I caught those references in the police station too. I wasn’t sure if it actually placed them in the same universe so to speak or what, but I liked it.

Jason: But yeah, the whole sequence of Fry hanging from Liberty’s torch is pure Hitch. You’re right about the special effects, but this ending felt totally right for this patriotic film. It might seem totally hokey, but it works. I like that Barry tries to help Fry, and the suspense of the tearing fabric is wonderful. The fall to his death was really well done for the time. Anyway, it struck me as the first of Hitch’s over-the-top American climaxes.

James: But how often do we need to see a hero slip up in a key scene by saying the other person’s name? I’m sure it wasn’t used to death by Hitchcock’s day, but when Pat says Fry’s name, I was like, c’mon. That’s always how they find out they’ve been had.

Jason: I’m not sure that was a slip-up. I think she deliberately decided to use his name to make him stop. She’s stalling him from leaving to catch the ferry, and it’s her last hope of giving him something to think about.

James: That makes more sense and makes the scene much better, actually. I like it.

Jason: Did you spot Hitch in his cameo? I saw him pretty easily, although it’s one of the brief, background kind.

James: You know, I didn’t even look for Hitch. Where was he? I think he’s on the back of the DVD case.

Jason: He’s in a street scene, at a newsstand, just reading. In New York. According to the documentary on the disc, he was originally supposed to do something much funnier involving nonsense sign language, with the writer, Dorothy Parker.

James: I would’ve loved to have seen that.

Jason: One of the books I’m reading talks about the contributions of Dorothy Parker, the novelist, and how some sequences, like the circus-freak scene and the blind-uncle scene, had her signature—a more literary quality. Hitch seems to like to bring in new writers, or at least values them tremendously. I know for his next film, Shadow of a Doubt, he brings in Thornton Wilder to help out with the “small town”-type story.

James: The Our Town writer makes sense for Shadow of a Doubt. I also think it’s interesting that Hitch’s wife Alma and his assistant Joan Harrison (who he brought over from England) are helping with the writing on a lot of his films.

Jason: Oh, you know what I thought was weird? Saboteur is this patriotic rah-rah movie, right? It’s all pro-American. And yet it ends with the absurd French “Finis” card at the end. What the hell is that about?

James: I hadn’t noticed that. Interesting. Anyway, in general, one part of me thinks this film is magnificent, and another part of me thinks the lack of wit and the lack of strong leading roles hampers it. Yes, it has a 39 Steps feel to it. And while it has plenty of propaganda messages scattered throughout, it works with the film, so it doesn’t feel forced or out of place to me.

I agree that the shot of the Normadie is confusing for anyone who doesn’t know about the Normandie incident, but I don’t think we’re supposed to think that Barry failed to stop Fry. After all, the movie quite clearly shows the ship upright after the bomb goes off. I think we’re meant to think that Fry’s group was previously responsible for a different act of sabotage which sank the Normandie. This probably would have been a lot clearer back in 1942, because the capsizing of the Normandie was big news and there were rumors of German sabotage.

What happened to Tobin? Lot of loose ends. The film finished too abruptly.