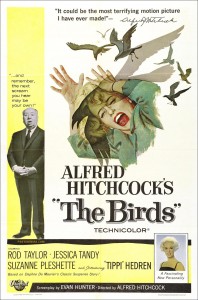

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

Synopsis: A wealthy San Francisco socialite pursues a potential boyfriend to a small Northern California town that slowly takes a turn for the bizarre when birds of all kinds suddenly begin to attack people in increasing numbers and with increasing viciousness.

James: Before we start, what do birds symbolize in Hitchcock’s films? Chaos? Uncertainty?

Jason: Birds have always symbolized exactly what you’ve said in Hitch films: Chaos. Uncertainty. Foreboding. Doom.

James: I must say—what a weird movie! I’ve never realized just how bizarre it is. I mean, before we see the first bird attack, you could call this film a straight-out romance flick. Then, it turns out that the romance is the MacGuffin, and the movie goes suddenly bizarre.

Jason: Yeah, The Birds is a strange bird. And as usual, this is the first time I’ve really watched this film. The thing that strikes me most about it is that it’s not any kind of traditional narrative at all. As you say, it starts out as if some kind of romance is brewing between the main characters, and then it morphs into this strange, episodic horror thing. The story starts breaking down in fits and starts, and by the end, there’s just chaos and doom. It’s really one of the strangest Hollywood films I’ve ever seen.

Jason: Yeah, The Birds is a strange bird. And as usual, this is the first time I’ve really watched this film. The thing that strikes me most about it is that it’s not any kind of traditional narrative at all. As you say, it starts out as if some kind of romance is brewing between the main characters, and then it morphs into this strange, episodic horror thing. The story starts breaking down in fits and starts, and by the end, there’s just chaos and doom. It’s really one of the strangest Hollywood films I’ve ever seen.

James: I know, it suddenly turns into something that Stephen King might have written as a prequel to Psycho. There are so many parallels between these two movies, it’s crazy.

Jason: Psycho parallels? I didn’t really catch many parallels, except for the climactic attic attack (say that three times fast). Can you elaborate?

James: Well, perhaps not parallels, but similarities. I actually watched The Birds as if the main male character, Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), was a kind of alternate-reality Norman and that his mom wasn’t (yet) dead. I could imagine a variation of the Psycho plot in this bizarro world, in which Mitch brings home a woman (or she comes of her own will) and the mother unconsciously brings doom upon them. I know it’s far-fetched, but that’s how I viewed the film, and it felt right, to some degree. And after the crisis he faces, I could see Mitch becoming this guy who likes to stuff birds—as therapy following the events of the film.

Jason: That’s an intriguing way to view the film. It’s obvious that Psycho was a huge influence on Hitch, and I’m sure he felt the need to live up to that success and even emulate it, in a way. So, yeah, Psycho was definitely on his mind.

James: Before we get into the progression of this film, let’s take a few minutes to figure out what happens in The Birds. Now, I recognize the symbolism of the lovebirds early in the film—representing Mitch and Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren)—and I see that Melanie is something of a caged bird herself, but as I watched this time, I came to realize that it’s really Mitch’s mother, Lydia Brenner (Jessica Tandy), who’s symbolically responsible for making everything happen in this film. Lydia simply can’t live without her son. It’s as if she brings this bird craziness upon them to rid their lives of Melanie, the potential threat to her family. The more I think about this notion, the more I dislike Lydia. But the timing of the bird attacks, combined with what we’re learning about the character, is nearly perfect: Every time Lydia sees Melanie and Mitch together, the birds seem to attack. This is probably a well-known theory, but I’ve never noticed it until now.

Jason: I had the same reaction while watching The Birds: What’s going on here? I just finished watching it a second time, in fact, and only now am I getting a vague handle on the film. One big clue that struck me happens toward the end. As the characters are holed up in their house (caged like birds), and the birds begin their attack on them, Mitch tries to fix a broken shutter and gets all bloodied up from the biting birds, which reach out toward his arm and pull at him as if clutching at him. After he fixes the problem and shuts out the birds, he backs into the room, and first Lydia and then Melanie pull at him as if clutching at him. I think it’s an obvious parallel, and it’s helping me think about the meaning of the film. Is it possible this whole movie is a study of Hitch’s favorite symbol? I mean, even more deeply than we even expected? The way I’m leaning now, the birds symbolize the “chaos” of women in Mitch’s life. You mention that you once thought the birds symbolized Melanie and that now you think they symbolize Lydia, but what if it’s both? Or rather, all the women in his life, including Annie, the schoolteacher, and Cathy, the little sister?

James: I guess I just think that the birds are brought by some sort of cosmic power. That sounds funny, but it struck me that almost all the bird-related events involve Melanie, and most of them occur right after Lydia sees her with Mitch. As for the girls in Mitch’s life symbolizing birds themselves, I totally agree. I’ve always seen Melanie as a bird to some degree, and I also recognize the irony of people in cages at the end. (This role-reversal is brought to the forefront in the restaurant scene, when the ornithologist talks about birds ruling the world.)

Jason: I want to dig a little deeper into when the bird attacks occur. They seem to happen in waves: Hitch gives us a dialog scene, in which we learn more about the characters, and then we get a bird attack. It’s possible that each bird attack is punctuating specific human interactions, but I haven’t made the jump to solving that riddle. I also noticed that the birds seem to target children a lot. That’s something that I couldn’t quite grasp the meaning of, and I thought it would be explored further. At one point, Melanie says, “I think they were after the children. To kill them.”

James: Yeah, I can’t quite figure out why they attack the children either. Maybe it’s something as simple as innocence? Or maybe children are the product of a loving relationship, and thus the birds (which are a symbol) attack them. But it’s hard for me to let go of the notion that Lydia, in some way, has brought on this destruction, so when I look at that question, I wonder about it through her eyes, so to speak.

Jason: Hmm, food for thought as we go forward … Now that we’ve sketched out some vague ideas, we should look at how the characters develop and maybe try to get a handle on how their relationships correspond to the assault of the birds.

James: Let’s go back to the opening scene, which I love. It’s light and fun, a great way to open such a bizarre horror flick. I love the banter about the lovebirds, and I like how this theme is carried throughout the movie. Every time we hear the term lovebirds, we see Marion and Mitch, and it’s obvious that the birds in the cage represent these two would-be lovers.

James: Let’s go back to the opening scene, which I love. It’s light and fun, a great way to open such a bizarre horror flick. I love the banter about the lovebirds, and I like how this theme is carried throughout the movie. Every time we hear the term lovebirds, we see Marion and Mitch, and it’s obvious that the birds in the cage represent these two would-be lovers.

Jason: First of all, my initial impression of the opening scene—in fact, the first 15 minutes—is that nearly every shot has a bird in it. We, the audience, are visually and sonically assaulted with the omnipresence of birds. They’re everywhere. I also noticed that there’s no score at all, there are only bird sounds. That’s a bit unsettling from the start.

James: The lack of a score in this film totally makes you realize how alone you can feel among all these birds.

Jason: But there’s something weird about the dynamic of Mitch and Melanie’s flirting in the bird shop. I think both characters give an extremely bad first impression. I don’t like either one of them. Melanie is this rich, spoiled, high-maintenance socialite who gets everything she wants. Mitch is this holier-than-thou, smirking, brash lawyer. Right from the start, their budding relationship is based on a lie—that of Melanie pretending to be an employee of the pet shop and Mitch not letting on who he is, either. I caught the lovebird symbolism, sure, but at first it seemed an ironic symbol.

James: Odd. I liked the dynamic immediately. I liked the playful attitude she has, most definitely. She seems spunky, like some of the earlier Hitchcock blondes. As for him, I liked his demeanor to a lesser degree, but I did nonetheless. Perhaps it was because he seems to balance her deception. It felt playful, either way.

Jason: Really? Wow, we took two totally different views of these early scenes. I sensed a lot of friction, even as I also sensed an undercurrent of attraction. I mean, she’s downright angry with him that he turns out to be a lawyer who holds her in seeming contempt. What is that courthouse back-story, anyway? Did you catch all that? You think Melanie is spunky? I think she’s a spoiled brat.

James: Yeah, I saw friction, too, but I saw it as a sort of flirtatious friction. You know, like when you were a kid and you picked on the girl you liked most. That kinda thing. But I definitely saw some chemistry. As for the court back-story, that’s just a touch on her personality to show that she’s mischievous and gets in trouble from time to time. But in reality, it’s like a mini MacGuffin … it means nothing.

Jason: Hmmmm. I think we’re really at odds here. I’m thinking about these characters right now, and I realize I know very little about them, and from what I do know—at least from the first act of the film—I don’t like them at all. Okay, I guess Mitch is okay, because he’s thinking about a nice gift for his 11-year-old sister, Cathy (Veronica Cartwright) back home. But everything else about him is off-putting. He’s way too close to his mother. He’s kind of a prick in his first interaction with Melanie, all smirky and know-it-all. And Melanie? Total bitch queen. True, she redeems herself a bit by pursuing him with the lovebirds he wanted. But overall, man, I didn’t like her. Nope.

James: Yeah, you’re completely wrong with this one. I actually thought he was more of a jerk than she was. But I appreciated them both. Sure, they were deceptive and almost rude to each other, but it was done with a flirty fun attitude. Plus, she’s pretty attractive, and that’s the type of woman I like.

Jason: I can see where you’re coming from, but I just don’t like those high-maintenance, nose-in-the-air society types that get everything handed to them and have come to expect it from everyone.

James: I can’t remember offhand, but isn’t there even a throwaway line about birds in a cage?

Jason: The only line I can think of about a bird in a cage is when Mitch says, “Back into your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels,” thus revealing that he knows exactly who she is. It also suggests to me that he thinks she’s a spoiled brat.

James: That’s the quote I was thinking of. For me, it marks the symbolism for the entire movie.

Jason: Oh, and by the way, this is when we get Hitch’s cameo, right up front, walking his own terriers. Not a bad cameo.

James: The cameos at this point in Hitch’s career seem a little bland, even forced. Sure, this one’s funny, but since he now gets them out of the way so quickly, so that his audience isn’t waiting looking, they don’t have the power the earlier ones did.

Jason: You’re right about the cameos. And this one would have been cooler had he been carrying out a birdcage …

James: Anyway, another thing I should note is that The Birds gives us one of the better-paced Hitch romances we’ve seen. Mitch and Melanie slowly grow to love each other, and I appreciate that.

Jason: I do agree about the pacing. Melanie very methodically follows Mitch to Bodega Bay, and we watch her every single-minded move in that direction. This part of the film, now that I think about it, is very similar to the first act of Psycho—Marion fleeing Phoenix and racing toward her lover, with no idea of what awaits her. In this case, Melanie is racing toward her would-be lover in Bodega Bay, fully embodying the MacGuffin, with no idea what awaits her.

James: I really liked Melanie the more I watched her. Pulling her little practical joke and driving all that way to Bodega Bay … I liked that. And the banter she and Mitch have later about her not driving out to see him in San Francisco … great stuff. Seemed real and fun and telling. By the way, as she drove, did you notice the lovebirds leaning right and left as she turned corners at high speed? That was hilarious.

Jason: I did notice that touch. Nice. But this is one Hitch flick in which the background process shots really disappointed me. After all, Hitch was really on location in Bodega Bay. Why not film these driving shots with some realism? The film is littered with obvious process shots, juxtaposed with some truly great on-location vista shots.

James: Yeah, those shots were a little sad, since we’ve seen he can do better. One thing I noticed was Bodega Bay’s water level. In her first scene on the water, Melanie paddles all the way across to the dock in front of Mitch’s house. The next morning, at the party, we see a wide-angle shot and the lake is almost dry.

Jason: I didn’t notice that about the water level in the bay. Nice catch. I guess I was too focused on the obvious process shots. They really took away from the drama of the scene for me. But before Melanie gets to the lake, we get the scene where she goes to the home of Annie Hayworth (Suzanne Pleshette), the schoolteacher, to verify the name of Mitch’s little sister, Cathy, so she knows who to address her card to. This is an important scene, because it sets up the rivalry between these two women, and we learn that Annie’s relationship with Mitch never really developed—because of Lydia. And through the whole scene, those lovebirds in the car go on chirping.

James: I love the way Annie and Melanie interact. It’s a quiet rivalry. Well done. And they never really say anything directly about it. Instead, it’s boiling under the surface.

Jason: There’s some good, fun tension to the scene in which Melanie stealthily brings the lovebirds to Mitch’s house across the bay. It’s interesting how she gets all the way across, then quietly runs up to the house, makes herself right at home by just barging in, leaves the birds, then runs off down to the boat. Then, Mitch comes upon the birds, dashes outside to see who left them, and spots her with his binoculars (beginning yet another Hitch motif of “seeing”). Loved the chase across the bay, she in the boat and he racing around in his car.

James: That chase across the lake is great. I laughed out loud when we see him speeding over and around those curves. I really liked him looking through the binoculars to see her, too. Nice touch, and good catch on the “seeing” motif, which we’ll see more of through this film.

Jason: Okay, here’s where we get the movie’s first bird attack. A seagull darts out of the sky and pecks Melanie on the forehead, drawing first blood. Now, if we’re looking at this film at a symbolic level, what provoked this first attack?

Jason: Okay, here’s where we get the movie’s first bird attack. A seagull darts out of the sky and pecks Melanie on the forehead, drawing first blood. Now, if we’re looking at this film at a symbolic level, what provoked this first attack?

James: Well, for me, the bird attack was simply provoked by Mitch’s sudden chasing of Melanie. Notice that it doesn’t happen until Mitch starts interacting with her. He has now, in the eyes of his mother, fallen for Melanie. Or taken another way, he’s beginning to no longer need his mother and is thus threatening to leave her alone—which Lydia fears most. That’s the way I see it. Not that Lydia really has this power, but that’s what it’s all tied to, symbolically.

Jason: Okay, so far I’m with you on the birds symbolizing the fact that Melanie is threatening the weird, fragile relationship between Mitch and Lydia. But is it going to hold up for the whole film? We’ll see.

James: So far, I can’t think of another reason for the timing of events.

Jason: One thing I found fascinating is when Mitch and Melanie go to the diner to clean her bird wound, and they start small-talking. Melanie lies again—the second time in their short little relationship—by telling Mitch that she just happened to be in Bodega Bay and that she’s staying with her friend Annie Hayworth. I wrote down in my notes, “This relationship is built on lies and smirky jokes.”

James: A relationship built on lies. We’ve never seen that in a HItchcock film before.

Jason: This is also the first time we meet Lydia, and the scene becomes full of this suddenly strange tension. She comes into the diner and is immediately suspicious of Melanie, giving her these long, cold stares and looking obviously troubled. When Mitch invites Melanie to dinner, you can see Lydia boiling beneath the surface. Trouble is most definitely brewing.

James: Yeah, at the diner, I immediately didn’t like Lydia. That’s when I equated her with Norman’s mother in Psycho—mean and needy and possessive.

Jason: And at the dinner scene later, Lydia makes sure to sit between Mitch and Melanie.

James: Ah, I didn’t notice her sit between them. Say, at the dinner scene, Lydia calls a man to talk about her chickens, which have been acting strangely. Is there a reason Hitch included this conversation other than to show that weird bird stuff is happening elsewhere?

Jason: I guess you’re right, it just shows that all kinds of birds are being affected. And significantly, these are all just common birds—nothing unusual. Chickens, crows, sparrows. But what’s interesting about this dinner scene to me is the overlapping dialog. Lydia is talking loudly in the foreground about those damn chickens, but in the background, Mitch and Melanie are small-talking. This is also when we see a portrait of Mitch’s father in the background. Melanie even remarks on it. We gradually come to realize how much of an absent figure he’s been in Mitch’s life, which is now completely dominated by Lydia—and, in fact, the influence of all women.

James: And Dad is looking right at us.

Jason: Later, we get the weird scene in the kitchen when Mitch calls his mother “darling” and “dear.” This happens a few times throughout the film. Just a little off-putting.

James: Mitch calling Lydia “darling” and “dear” is just plain odd. It made me think that a little something more was going on between them than the typical mother/son relationship. Hahaha. But it actually heightens the emotional connection they have. Or rather, the connection that she needs. It’s as if he’s filling in as both the father and son in their relationship. Which is very powerful indeed, because she sees him as both and needs him as both—and that heavily influences her hatred of any other woman who wants to spend time with Mitch.

Jason: A little later, Lydia even tries to discredit Melanie by bringing up the little item she read about in the gossip paper: Melanie once jumped nude into a fountain in Rome. She’s trying to bad-mouth Melanie, but man, if I were Mitch, that would make me all the more hot for her.

James: I like how Melanie shrugs off the account of her in Rome by saying she was wearing clothes and was pushed. Sure, she has fun and does crazy things, but it’s interesting that this one instance can be seen in two different ways, depending on who’s thinking about it: Lydia considers her a tramp, while in reality, she was pushed.

Jason: Melanie does admit she runs with a wild crowd. And I got the distinct impression that she’s lying when she says she had her clothes on and was pushed. Mitch even makes fun of her: “You’re just a poor, innocent victim of circumstances, aren’t you?”

James: Why do you think she lies about that? I didn’t catch that at all. I think you just don’t like Melanie.

Jason: Yeah, maybe I just don’t like her. But it’s a definite impression I got. Why should we assume she’s telling the truth? Not that it’s a big deal, but we can’t be sure she’s giving us the facts. I mean, she’s already lied twice.

James: Fine, fine.

Jason: What did you think of Cathy? She’s played by Veronica Cartwright, who’s still working. She played Lambert in Alien and was in The Witches of Eastwick. I thought she gave a convincing performance here.

James: Cathy was okay. She’s a typical Hitchcock kid who’s cute on one hand but totally annoying on the other.

Jason: Now we get to the scene where Melanie gets the scoop on Lydia from Annie. We learn that Lydia’s not necessarily a bad person, just hugely possessive, afraid of being left alone.

James: I like the scene with the two women. Great interaction, especially the way they don’t really talk about anything at first. They both know what’s under the surface of their conversation, but neither is going to talk about it. Learning the truth about Lydia is almost spooky. Lydia continues to come across as a nutjob who can’t live without her son.

Jason: I guess this is more fuel for your argument that Lydia is the driving symbolic force behind the bird attacks. They represent her inner turmoil when anyone threatens to take Mitch away from her? I just think there’s more to it than that.

James: What more could you want? What else is driving these birds to Bodega Bay?

Jason: I just think there’s more to it. Why do the birds attack the entire town? Why do they seem to target the children?

James: I’m not saying it’s an airtight explanation for the events, but what else do you have?

Jason: No, no, I’m just saying I want to finish talking through this movie before we finally decide what this “whole film” symbol really represents.

James: Well, I don’t want to get it wrong about what I’m saying. I agree with you about what the birds symbolize. I like the idea that they represent the hectic nature of Mitch’s women. I’m just saying what I think is the reasoning for the birds coming. I think they are two different things.

Jason: Well, we get the second bird incident right at this point—a dead bird on Annie’s porch. You know, at this point, Annie says “Poor thing” about the dead bird. Have you noticed how often people say that in Hitch’s films? I’ve noticed it a lot, but right now I’m flashing on Midge saying it in Vertigo about Carlotta.

James: Never noticed that.

Jason: How about the odd moment between Mitch and Melanie, on the hilltop above Cathy’s birthday party the next day, when Melanie talks about her mother “ditching her when she was 11″? There’s a lot of repressed anger there. And this moment is immediately followed by the third bird attack, as the kids play (as in Young and Innocent) “Blind Man’s Bluff.” Is there something to this conversation about Melanie’s mom?

James: I think the conversation about Melanie’s mom “ditching her” does two things. First, it sets up a possible reason for her becoming a wild child, and second, it helps us make a certain leap when she helps Lydia after her breakdown later. In a way, Lydia becomes Melanie’s mother, and Melanie can connect with Lydia in a way she never could with her own mom.

Jason: You make an excellent point about Lydia becoming the mother figure that Melanie has been missing. Which is all the more interesting because it’s clear the Lydia hates Melanie through most of the film. By the end of the film, there’s definitely a mother-daughter aspect to their relationship. And isn’t it interesting that they look so much alike?

James: Hmmm, interesting!

Jason: Even their hairstyles are similar.

James: The third bird attack happens almost immediately after Lydia notices Mitch and Melanie walking down from the hill.

James: The third bird attack happens almost immediately after Lydia notices Mitch and Melanie walking down from the hill.

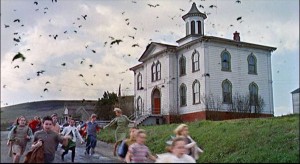

Jason: So, in this attack, the birds target the children at Cathy’s birthday party. What did you think of the special effects? I have to admit that they look dated, but for the time, they must have been elaborate and impressive.

James: I thought the effects were good at times, but really dated in others. When the actors have fake birds pecking at them while they run on a treadmill … that’s bad. But man, in the next scene, when all those birds flood into the house from the fireplace, or later when the birds keep landing and perching on the roof or the jungle gym … great stuff.

Jason: You’re right, some of the process shots of the kids running while being attacked are poor. I wonder if audiences of the time were more accepting. Anyway, the film segues right into the fourth bird attack, when the sparrows spew out of the fireplace and fill the room, dive-bombing the family and Melanie. I can’t remember, but what do you think triggered this particular attack? Just the fact that Melanie is still among them? Still between Mitch and Lydia?

James: I’d have to watch that scene in their house again. If I remember correctly, there’s another reference to lovebirds, with the camera firmly planted on Mitch and Melanie, right before the storm. But man, that scene is spectacular.

Jason: Yeah, the living-room attack is extraordinary, especially for the time, and particularly when you consider that those actors are reacting to nothing for most of the scene. All those birds were optically inserted later!

James: I absolutely loved how dumb the sheriff is, after this attack. He keeps doubting everything the family says. It’s both funny and painful—painful because he’s such a dullard, and it’s hard to watch him bumble through such an obvious investigation. (Here’s another incompetent cop from Hitch.) Sure, he says, a bunch of birds … you don’t see that every day.

Jason: That sheriff is hilarious. But what I find most interesting about this scene is the way Melanie’s gaze is so intent on following Lydia’s every move as she walks slowly to some broken china on the ground and delicately picks it up. Why this weird point of view? I’m stumped by this scene. Is Melanie finally making a connection with Lydia, empathizing with her? Or is there something to what Lydia is doing?

James: That is a weird point of view, but like you, I saw it as Melanie realizing that Lydia is a tragic figure, not someone to despise or hate. In a way, it’s almost as if she’s looking at her own mother and learning that there shouldn’t be any animosity there.

Jason: I think it’s very telling when a bird feather falls from the portrait of her dead husband when Lydia adjusts it on the wall.

James: I agree. That is very interesting that the bird feather falls from the portrait. I’m not sure what it means, but yeah.

Jason: I just think the falling feather emphasizes the absence of the father in the whole dynamic. And it also reminds us that he’s dead.

James: Word.

Jason: So how about the scene in which Lydia goes to see farmer Dan and finds him murdered by birds, his eyes pecked out? First of all, I like that this is another practically silent sequence. I like the suspense leading up to the discovery, and I especially like Lydia’s panicked reaction to what she finds. It’s a grisly scene in there.

James: I love that scene for the exact reasons you state. It’s silent, which allows us to feel the moment a lot more. Walking around the corners, first seeing a hint of what happened, then seeing a dead bird at the window, then the dead body … right up to seeing his eyes pecked out. I loved it. It reminded me of the reveal in Psycho, when we see Norman’s mom’s eyes are gone (obviously). I think Hitch is saying something in both films, now that I think about it: The farmer can no longer see the evil in this town? I don’t know, but it’s powerful regardless.

Jason: As usual in Hitch’s films, there seems to be a lot of seeing and watching (or not seeing and not watching) in this film. I wonder how that ties in to the whole of this film.

James: You’re right, of course, everyone is watching in this film. Even the father is watching from the painting on the wall.

Jason: Nice catch!

James: This is the only death/attack that’s hard to explain in the context of Lydia being the bringer of the birds. At first, I thought Dan was the farmer who sold the feed to her, which could explain it. But instead, it’s another farmer. I’m sure I could make some sort of leap here, but no matter what I think, it seems far-fetched. I’d have to watch the film again to get the link, but maybe there is none.

Jason: I love the moment when Lydia flees back home, following her grisly discovery, and sees Mitch hanging out with Melanie. She breaks away from them in disgust, hurtling herself into the house. Apparently, not even the horror of the dead man with the eyes plucked out can alleviate how threatened she feels by Melanie. And yet, in the next big scene, Lydia delivers this long monologue to Melanie, and it’s really the turning point in their relationship. She says, “I feel as if I don’t understand you at all and I want so much to understand … I don’t even know if I like you or not … Mitch is important to me. I want to like whatever girl he chooses … But, you see, I don’t want to be left alone. I don’t think I could bear to be left alone. I don’t know what I’d do if Mitch weren’t here …” So, right there, from Lydia’s own mouth, we get the main thrust of the film.

James: I’m a bit torn on that scene. It feels a little fast. Sure, this devastating thing just happened, but I found it a little hard to believe that she’d open up to Melanie so quickly. But it does help solidify the relationship, and it’s a nice scene to propel us into the action of the rest of the movie. I do like how Melanie asks why Lydia thinks she has to like the girls that Mitch likes.

Jason: It does feel a bit fast. Maybe she needed the trauma before she could open up emotionally. She needed someone to talk to, and Melanie was the only one around. And I like the scene, too, except that you’d think the symbolism would follow through and the bird attacks would calm down, but in fact, they intensify. This is really when the film starts going nuts—it becomes this weird assemblage of gonzo bird-attack scenes punctuated by dialog scenes. I’m loving the free-flowing nature of it, but you gotta admit, it doesn’t make any goddamn sense.

James: Yeah, this movie really makes no sense whatsoever.

Jason: When you think about it, The Birds is probably Hitch’s craziest movie.

James: I really like how the school scene develops. Watching Melanie sit on that bench, waiting for the class to get done while the birds start gradually amassing on the jungle gym … that’s so great. The tension is drawn out perfectly.

Jason: The scene at the school is the movie’s most famous sequence. Again, it’s played silently, except for that strangely haunting rhyme that the kids are singing in the classroom. The birds quietly amass, and then we get the terrific reveal, as Melanie finally looks behind her to see thousands of birds everywhere. Delicious.

Jason: The scene at the school is the movie’s most famous sequence. Again, it’s played silently, except for that strangely haunting rhyme that the kids are singing in the classroom. The birds quietly amass, and then we get the terrific reveal, as Melanie finally looks behind her to see thousands of birds everywhere. Delicious.

James: Yeah, after she sees what’s behind her, the way she walks carefully back, trying not to make a sound … very intense. Of course, some of the shots of the kids running down the street with birds pecking at them looked silly. Back then, maybe not so much. But now, man, those are dated.

Jason: I’d still say it’s an effective sequence, despite the dated effects. The kids look genuinely scared, and there’s a horrifying unrealism to the shot, as if it’s “stylized terror,” if that makes sense. It’s almost as if the effects give the drama a heightened realism. Yes, it’s unrealistic in one sense, watching kids run in place in front of a process shot, but it puts the kids right in your face, battling in extreme clarity with these crows.

Jason: You’re reaching, man.

Jason: Yeah, I guess so. Now, the only thing I can think of as far as the symbolic provocation for this attack on the kids (including Cathy), is Lydia’s fear of losing both her children, not just Mitch. What do you make of the moment when one of the kids falls, shattering her glasses? More evidence of the theme of “not seeing.”

James: The busted glasses certainly bring up the “not seeing” motif. Always seems to. But not seeing what? That’s what I don’t get.

Jason: Not seeing what—that’s the question. Maybe by the end of this little discussion, we’ll see what we’re supposed to see. Maybe it’s just Hitch’s way of saying, “This isn’t really just a movie about random bird attacks with no explanation. If you can’t see that, then you’re blind. This movie is about subtext and symbolism. It’s not about seeing but rather understanding.”

James: What did you think of the second scene in the diner? My question is, Where did all the kids go? But regardless of that mystery, the diner reminded me of Jaws. It’s a small fishing town with some menace taking place just outside. And in this diner, there are people debating the whole thing. The old woman—Mrs. Bundy (Ethel Griffies), the ornithologist—boy, I could just kill her. But I do like how every personality type is there to discuss this crazy scene.

Jason: Interesting Jaws parallel. I can totally see that. And I completely agree about Mrs. Bundy—man, what an annoying, know-it-all character. And I think Hitch intended her (along with that drunken fool shouting, “It’s the end of the world!”) to be both informative and comic relief. But that damn beret, that suit, the way she smoked and talked—oh hell, get her away from me. I do like how she’s shamed into silence after the birds do, in fact, start attacking humans outside. This is also when Melanie talks about the school attack: “I think they were after the children …. to kill them…”

Jason: Interesting Jaws parallel. I can totally see that. And I completely agree about Mrs. Bundy—man, what an annoying, know-it-all character. And I think Hitch intended her (along with that drunken fool shouting, “It’s the end of the world!”) to be both informative and comic relief. But that damn beret, that suit, the way she smoked and talked—oh hell, get her away from me. I do like how she’s shamed into silence after the birds do, in fact, start attacking humans outside. This is also when Melanie talks about the school attack: “I think they were after the children …. to kill them…”

James: And what follows is the craziest attack yet, with explosions and wrecks and people running around screaming. Weird.

Jason: So, yeah, all hell breaks loose outside, and it’s really quite an impressive bit of chaos. I love the swooping bird that knocks the guy at the gas pump to the ground. I love the extreme overhead shot of Bodega Bay and seeing the birds hovering in the immediate foreground, ready to descend in their attack. It’s such a great, apocalyptic shot. The car explosion, with the guy getting incinerated before our eyes—nicely done! What did you think of the three shots of Melanie’s changing expression as we watch the chaos unfolding before her?

James: That was terribly done, I thought. Why not watch her watching the scene, going through her horror, instead of flashing on stills of her with different expressions? Seemed so wrong, for whatever reason.

Jason: I didn’t like that three-shot effect either. Seemed too artificial.

James: I did like the shot of Melanie in the phone booth and the bloodied man trying to get in. Excellent. She’s trying to protect herself, so she can’t let this man in.

Jason: The great part about Melanie inside the phone booth? She’s in a cage! The roles have again been reversed. Just as Mitch foreshadowed at the pet shop, “Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels.” She’ll be in another cage soon, locked up inside Mitch’s house and attic. I sure liked the shots of birds crashing into the side of the phone booth—very dramatic and frightening.

James: Nice catch on the cage. I hadn’t thought of that in the phone booth. Great stuff. This scene is probably the craziest of all the Hitchcock flicks. It’s so out there. Wild. Crazy. Hectic.

Jason: My question, though, is why do these people even venture outside? Seems like Melanie, for example, would have been just fine if she’d stayed in the diner.

James: Why did they go outside? Good grief. And tell me why the woman with the kids wouldn’t know how to get on the highway. If she lives there, she’d know. If she wasn’t from there, she would’ve gotten there from the highway.

Jason: That’s a good point about the woman with the kids. Didn’t even think of it.

James: Lame.

Jason: When the attack subsides, Mitch and Melanie go back into the diner and find a group of women huddling in a hallway. What do you make of this little monologue, from the woman with the kids: “Why are they doing this? They said when you got here, the whole thing started. Who are you? What are you? Where did you come from? I think you’re the cause of all this. I think you’re evil. Evil!”

James: That quote actually fueled my thinking that Lydia is bringing the birds into the town—that once Melanie arrived, right when Mitch was in danger of leaving, the danger began.

Jason: Now Mitch and Melanie go to get Cathy, who—for some unexplained reason—is with Annie at her home, rather than being with Melanie, as she promised Lydia earlier. They find Annie dead of yet another bird attack. She supposedly saved Cathy at the expense of her own life. I was actually surprised by this death. It’s so unexplained and unexpected. You?

James: I hadn’t considered the fact that Cathy was with Annie. Hmmmm. I wonder. That’s a fault of Melanie’s, then. Her priority should’ve been that kid. As for Annie’s death, I liked that it was off camera.

Jason: When Mitch and Melanie take Cathy home, they begin boarding up the house for the big finale—and, as I said, creating their own “bird cage.” And we also get some conversation about how the attacks are happening for no reason at all. To me, that’s one of the most interesting aspects of this film: There’s just no explanation, which leads us to examine the film much more deeply than we would otherwise, and search for symbolic meaning.

James: What’s the meaning then? I don’t even see the need for a meaning. It’s crazy. It’s inexplicable. I still stand by my assumption that Lydia is somehow to blame, but I don’t think it needs to be delved into and completely figured out.

Jason: Maybe the big attack and Annie’s death have a little to do with the fact that Melanie broke her promise and left Cathy alone with Annie? Anyway, just before the attack, I noticed another scene in which Melanie watched Lydia cleaning up teacups. Did you notice this? It’s another obvious point-of-view shot of Lydia taking care of this little domestic chore. Very interesting.

James: Melanie watching Lydia again. Hmmm. I did notice it, but I don’t really have a reason for it. Maybe it’s Melanie’s own motherly instinct coming into play? She wants to protect Lydia, unlike her own mother?

Jason: The final attack on the house is interesting because we hardly see any birds at all. The suspense is generated mostly from the sound effects and the acting. And this is the scene I mentioned early on in this conversation, when Mitch is bitten by a bird at the window, and both Lydia and Melanie reach for him, as if pulling at him.

James: That ending is great. So suspenseful. The fact that we only hear the millions of birds outside … it’s so apocalyptic. I knew the outcome of the scene, but I was still riveted. I was actually scared for these people, trapped in their cage.

Jason: And finally we come to the Psycho-influenced bird attack on Melanie in the attic. She hears some scuffling above her, and she climbs slowly up the stairs (once again, stairs represent doom) toward hell. I think it’s very effective how—true to the rest of the film—this scene is all sound effects: fluttering wings, squawks, her heavy breathing and yelps.

Jason: And finally we come to the Psycho-influenced bird attack on Melanie in the attic. She hears some scuffling above her, and she climbs slowly up the stairs (once again, stairs represent doom) toward hell. I think it’s very effective how—true to the rest of the film—this scene is all sound effects: fluttering wings, squawks, her heavy breathing and yelps.

James: Come on, that scene with Melanie upstairs … how stupid. Why in the world would she go up there and open the door? And why does she go fully into the room when just looking would’ve sufficed? I hated that to no end. Sure, we need her to get hurt or to be saved or blah blah blah. But man, she came across as an idiot by her actions.

Jason: Hmmm, I didn’t look at the scene from that angle. But now that I think about it, it is indeed stupid of her to go up there alone. It almost seems as though she has to go through it. Like Marion’s shower in Psycho, this is Melanie’s “baptism,” which allows Lydia to finally care for her and nurture her. But you’re right—on the surface, she comes across as idiotic.

James: Interesting.

Jason: And when Mitch and Lydia rescue her, Lydia says, “Poor thing.” A familiar phrase, and Lydia’s ultimate acceptance of her among the family? Say, when they get Melanie to a couch downstairs, what did you think of Melanie’s little freak-out, when she looks directly at the camera and starts shielding herself madly?

James: I didn’t particularly like that freak-out. I liked the idea of it, but it didn’t work that well. Wasn’t that well acted.

Jason: It does feel a little cornball. Maybe if she hadn’t been looking directly at the camera … but then we wouldn’t have the carried-through symbolism of “seeing.”

James: Another lame moment: Cathy demands that she bring the caged lovebirds with them as they escape the house. I can see this as a need to keep something normal, or that it represents the old world in which birds were in cages rather than humans, but it still didn’t sit right with me.

Jason: Cathy keeps bringing up the lovebirds in their cage, and throughout the film, they’re just fine—just normal birds. I guess they represent rational behavior, maybe even the hope of a return to normalcy. So the fact that she insists they take those two birds ends the film on a small note of hope.

James: All that said, the scene with the family and Melanie driving off, birds everywhere … how wonderful is that? I mean, that’s no happy ending. That’s truly frightening.

Jason: What a magnificent shot! Millions of birds reaching into infinity. And it’s a special effect that really holds up. That, combined with the quiet and the minor bird sounds, adds up to an extremely suspenseful and surprisingly open-ended finale. (I read that Hitch refused to insert a The End card.) When the film fades out on this shot, I was blown away by how the film had become this crazy free-for-all non-narrative. This film just doesn’t end. It doesn’t really have a middle, either, just a bunch of bird attacks and flailing people after the first act. It’s really somewhat mystifying.

Jason: What a magnificent shot! Millions of birds reaching into infinity. And it’s a special effect that really holds up. That, combined with the quiet and the minor bird sounds, adds up to an extremely suspenseful and surprisingly open-ended finale. (I read that Hitch refused to insert a The End card.) When the film fades out on this shot, I was blown away by how the film had become this crazy free-for-all non-narrative. This film just doesn’t end. It doesn’t really have a middle, either, just a bunch of bird attacks and flailing people after the first act. It’s really somewhat mystifying.

James: Interesting note about the end card. I’m glad he didn’t add that. The way it ends now feels so open-ended. The car driving off slowly, all the birds … we know this continues. Life goes on. There is no real ending. I liked that.

Jason: And in the midst of all those thousands of birds, we get the significant shot of Melanie grasping Lydia’s hand inside the car, and looking up at her as if she’s the mother she never had. And they smile at each other. And the birds let them pass.

James: What a great ending. I loved it. All those birds. All those unanswered questions. Only a touch of the happy ending, which you note with the moment of the two women comforting each other. Great stuff.

Jason: I like our “reading” of this film: The bird attacks are symbolically linked to the power that Lydia holds over her children. Melanie is seen as an interloper early on, and as she gets closer to Mitch, the attacks increase in ferocity. Because Melanie also represents a threat to Cathy, forcing Lydia to potentially “share” the child in the family dynamic, the birds target Cathy and the children too. Because Annie represented a threat, she’s dispatched. But I want to suggest that the attacks represent something larger, too, and that’s the chaos of women in Mitch’s life: He’s pursued by Melanie and Annie, he’s hounded by Lydia, he’s depended on by Cathy—he lives in a world dominated by women (sometimes nicknamed “birds”). We’ve also talked about Melanie’s search for her lost mother, so that plays a role. I think it’s more the interplay of the three central characters—Mitch, Lydia, and Melanie—that sparks the assault of the birds.

James: I think we made more of this film than most. I mean, it’s hectic craziness. I agree with what we’ve discussed, and I like that we could bring meaning to it all. Makes for a far more entertaining film.

Jason: Definitely an unpredictable film, and I admire its narrative craziness and openness to interpretation.

Veronica Cartwright, who played Cathy Brenner in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, is scheduled to appear at the 2014 Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention, Hunt Valley, Md., at the Hunt Valley Wyndham Hotel, Sept. 18-20. She will be attending a screening of the film, and will be available for questions, photos, and autographs. More info http://midatlanticnostalgiaconvention.com

Great conversation guys really enjoyed it thanks!! Jo

Very interesting talk. James at one point notes how the woman in the restaurant doesn’t know how to get to the highway. Actually, they’re discussing the freeway and this is important as far as a comparison between The Birds and Psycho is concerned: Remember how Marion mistakenly takes a turn-off that leads her off the main (meaning new) portion of the highway and onto the old, disused highway that passes by the Bate’s Motel? Early in the Birds, Marnie is engaged by a tenant across the hall from Mitch’s flat in San Francisco when she is about to leave the caged lovebirds outside his entrance. The neighbour also informs Marnie that Mitch is not due to return until after the weekend. In the course of the ensuing exchange, he tells her that she can reach Bodega Bay either by freeway or by using the highway, which is described as coastal, explicitly narrowing the respective travelling times for each route down to half-hour increments. This precision in the screen play is suggestive of a deliberate attempt at directing attention to the reference. Melanie ends up taking the highway, taking on the bends in rally-driver style, much in character with her playgirl persona.

Interesting “take” indeed about the power plays of Lydia symbolic of the aggressive birds. I beg to differ, however, and have always considered the caged love birds as to true cause of chaos.

The first deliberate attack was on Melanie in the boat after delivering the lovebirds. Now, I accept that their was not a screenshot of any bird “seeing” this delivery, but sounds of birds are heard beyond the lovebirds chirps.

Secondly, the old bat (ha, sorry I don’t recall her name) in the restaurant with the cap on posturing somewhat as a male) was insistent about the true nature of birds being non-aggressive. She also states that if bird species were ever to flock together, humankind would have no chance. The ending has them driving off, with the lovebirds- which is a significant aspect of the story. Various species of birds crowded together watching, they did nothing to stop them from leaving with the lovebirds. What would have happened had they left without taking the caged lovebirds? I guess we’ll never know!

It seemed very intentional of AH adding emphasis to their leaving the house in the finale, of Cathy asking if she could take the lovebirds with them. Her subsequent line of “they won’t hurt anyone” (or “anybody” I forget which) was absolutely a significant statement.

Another comment about the lovebirds was made after the house was boarded up and the family and Melanie were waiting for the next attack. The lovebirds were in the kitchen and Cathy asks to go get them and defends the innocence of the lovebirds. Lydia says no, emphasizing that they are still birds.

So, my premise is still left with a large hole in the middle. Did the lovebirds intentionally communicate to to birds in the wild that they were caged and gave the call for a massive “uprising” against this human endeavor? Or did the birds in the wild “see” this without any communication whatsoever with the caged birds and they took it upon themselves to mass together and attack? Either way, the intentional timing of the first attack, after the birds saw Melanie leave the caged birds at Lydia’s- dropped off as opposed to released in the wild, seems important that is was in fact on Melanie.

Was Melanie “evil” in someway as the mother of the two kids declared during her emotional outburst in the diner? The mother was on the right track I think, but the evil was not inherent in Melanie but her action of delivering caged birds

Again, if my premise holds water, there are still a lot of holes for ambiguity!

Thanks for a great analysis of the “why” of the movie. Figuring out the “why factor” or motivation behind AH’s movies is of course what he wanted;)

I’m coming late to these Hitchcock discussions. I just rewatched “The Birds” a couple days ago — saw it on TV many years ago when I was about 12. Fascinating feedback. I had never thought of Lydia as causing the bird attacks — and I still don’t buy that promise, but you’ve got me considering it. I’ve always thought Melanie caused the bird problems, so when she gets accused of that in the diner later, I nod in agreement even while I can’t say why or how. Hitchcock loved getting his male protagonists into impotent situations, and that definitely holds true with “The Birds.” The apocalyptic ending? Perfect. I agree with the frozen shots of Tippi Hedren — I thought they looked dopey in the late 1960s when I first saw the movie as a kid, and I still think so today. But love-love-love the chaos and the trapped-in-a-cage scene at the gas station with Melanie trapped in the phone booth. Fantastic chaos. And with our climate crises of today, this movie still feels fresh — birds and insects and trees and oceans would be SO much better without humans and yet we’re still as smug as Mitch and Melanie were at the beginning of the film. Love it.

Meant to type “premise,” not “promise.”

As a child I watched the birds many times. At the end in the car I am sure that when grabs Lydia hand and looks up at her she says mother.

Why as I watch the movie now is this cut out. It is very significant.

I ment to say Melanie. Sorry.